The Caylor Tax Court Case

Introduction

A few months ago the IRS won its fourth recent victory against small captive insurance companies. Alas, this latest case does little to clarify the rules of the road for taxpayers, and the IRS seems to like it that way.

Rather than ending the “abuse” that it so frequently laments by simply providing the captive insurance industry with the definitive guidance that it has long requested and that Congress long ago demanded, the IRS prefers to continue beating up the weakest kids on the playground and then demanding lunch money from all the others.

The Caylor entities case shares two things in common with the three losing cases that came before, 1) their captives did not have adequate risk distribution; and 2) their captives did not act as insurance companies in the commonly accepted sense. The circumstances of this case in combination with the shrewd sarcasm of Judge Holmes make the opinion amusing read.

Background

Bob Caylor started Robert Caylor Construction Company (“Caylor Construction”) in 1961. Bob’s son, Rob, began working for his father at a young age and eventually formed Caylor Land & Development Company (“Caylor Land”). Where Caylor Construction was a commercial construction company, Caylor Land did commercial and residential contracting and consulting. Both businesses were successful and continued to grow, and ten subsidiaries formed. For a while, Caylor Construction bought third-party insurance, possessing “the broadest policies available in the commercial-insurance marketplace.” (*8). However, this insurance did not cover some significant losses experienced by the Caylor entities (nearly half a million). Rob was introduced to captive insurance in 2007 and quickly became interested. After seeking advice and conducting some research of his own, he formed a captive insurance company called Consolidated, Inc. in 2007. Rob was its owner.

An Odd Order of Events

On December 20, 2007, Consolidated made the election to be a U.S. corporation for tax purposes as well as the 831(b) election. However, “that same day Caylor Construction paid Consolidated $1.2 million, which it deducted as an insurance expense on its 2007 tax return.” The court said that “this was at least a bit odd, since Caylor Construction had not yet completed any underwriting questionnaires, and perhaps even odder because Consolidated had not yet underwritten or issued any policies to any of the Caylor entities.” The court further observed:

“[W]hat really made this first year remarkable was that the 2007 policies that Consolidated finally got around to issuing in 2008 were “claims-made” policies, which means that any claim had to be reported during the applicable policy period (or an extended reporting period of no more than 60 days). So when Caylor Construction paid $1.2 million at the end of 2007 to Consolidated – the same amount it would be paying during the years at issue for a year’s worth of coverage – in reality, it was receiving at most 10 days of coverage and possibly none at all… [A]s in 2007 the underwriting process for 2008 did not begin until after the 2008 coverage period had already closed… [but] these oddities in the 2007 and 2008 policies are not our focus because the tax years before us are 2009 and 2010. During both those years that Caylor entities also carried traditional commercial insurance.”

It should be noted, however, that traditionally a given coverage period begins after a policy is created and received.

2009 and 2010

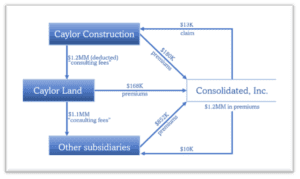

In 2009 Caylor Construction paid $1.2 million to Caylor Land for what they called “consulting fees” (which were deducted as consulting expenses). Caylor Land then paid $1.1 million presumably of this same money to the rest of the Caylor subsidiaries as “professional-consulting fees.” In the meantime, Consolidated received $180K in “premiums” from Caylor Construction, $168K from Caylor Land, and $852K from the remaining subsidiaries (which, oddly, were not independently or directly underwritten under Consolidated’s policies). Exhibit 1 illustrates the flow of funds.

Notably, the consulting payments to most entities made up the majority of their revenue, and these payments also closely matched the corresponding premium payments to Consolidated. In the years under audit, Consolidated was paid a total of $2.4 million in premiums, yet only had paid out $23,000 in claims – not even 1% of Consolidated’s income, resulting in a profit margin of over 99%

Moreover, the claims themselves had some issues. The first claim was for $13,000 in legal fees paid by Caylor Construction. Tribeca, Consolidated’s third-party manager, never received the support from Caylor Construction it requested to validate the claim. Rob and Paula overruled Tribeca anyways, and Consolidated paid the claim. The second claim was for $10,000 to La Playa (one of the Caylor subsidiaries) and was handled in much the same way. Tribeca again requested proof of documentation for these claims, which it never received. Tribeca again was overruled and Consolidated wrote the check.

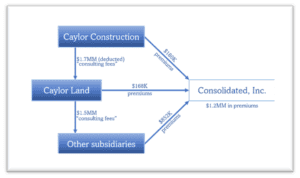

Exhibit 2 illustrates the flow of fund for the 2010 year, which was similar to 2009. The structure is very much the same but for a notable and unexplained increase in these mysterious “consulting fees” to Caylor Land from $1.2 million to $1.7 million, leading to an increase in the “professional-consulting fees” to the remaining subsidiaries from $1.1 million to $1.5 million. Consolidated received a total of $1.2 million in premiums from the Caylor entities, and this time, paid out no claims.

The “Consulting” Fees

Perhaps the oddest thing about the Caylor captive arrangement is those “consulting fees.” Again, these consulting fees represented the bulk of the revenue received by the Caylor entities during the course of the years and were used to pay large premiums to Consolidated that amounted to $1.2 million for both 2009 and 2010. When asked to substantiate the basis for those consulting fees,“[n]either one could say what this consulting concerned, what subjects they discussed, or the amount of time they spent talking business instead of the ordinary subjects fathers and sons talk about.”. In fact, without their testimonies, there is no evidence that the consultations happened at all, or why they were at such an exorbitant cost. As Judge Holmes eloquently noted “[f]or a father and son to have a warm and loving relationship that helps sustain and grow the family business is admirable. But it’s not deductible.”.

Risk Distribution

Judge Holmes also noted that “[i]n each of [the] previous microcaptive-insurance cases the captive tried to show risk distribution by investing in an ‘insurance pool’ – a way to reinsure a large number of geographically diverse third parties.” In Avrahami, Reserve, and Syzygy, the Tax Court found that the arrangements claimed to be “insurance pools” were not technically insurance; thus, there was no risk distribution. This case is unique in that, despite Tribeca’s recommendation, there was no real attempt to pool risk with other insurers at all.

However, it is still possible for a captive to achieve adequate risk distribution if it provides policies for to a sufficient number of brother and sister entities and insures a sufficient number of risk exposures. Per Judge Holmes “[t]he question is not solely about the number of brother-sister entities insured, but the number of independent risk exposures.”

Unfortunately for the Caylors, an insurance expert testified that “the risks faced by Consolidated – the 12 independent exposures for administrative action, 11 independent exposures for loss of key contract, 10 for cyberliability, and 1 for extended warranty – made for much too small for a risk pool.” The expert also pointed out that “all of the risks that Consolidated faced were heavily tied to one entity – Caylor Construction. The strong correlation of risk between the smaller Caylor entities and Caylor Construction prevented Consolidated… from having adequate risk distribution.”

In response to this, the Caylors contended that risk distribution can be achieved if 1) one insures a large enough number of unrelated risks so that the law of large numbers may predict expected losses; 2) the 12 entities possessing risks do not have liability coverage less than 5% nor more than 15% of the total risk insured by the insurance; or 3), 30% of the risks undertaken by the insurance company are from unrelated parties. Judge Holmes wasn’t buying it for the following reasons:

- The Law of Large Numbers

Judge Holmes noted that “[d]uring the years at issue there were at most 12 independent exposures for administrative-action and legal-expense reimbursement; 11 independent exposures for loss of key contracts; 10 for cyber liability, miscellaneous professional liability, and professional services reimbursement; and 1 for extended warranty.”Compared to the number of unrelated risks from other cases (that would allow the law of large numbers to predict losses), the Caylor entities’ risks were extremely small. Inn the Rent-A-Center case, for example, which taxpayers won, its captive “insured 14,000 employees; 7,000 vehicles; and 2,600 stores.”While admitting that there is not necessarily a precise number in order for the law of large numbers to apply Judge Holmes noted that “[it] is called the law of large numbers – not small numbers or some numbers.” Clearly, the Caylor numbers were not “large” enough.

- Liability Coverage

For the Caylor entities, “the risk insured – as determined by the taxpayers’ own expert – was extremely concentrated in just two companies, while the rest only had minimal risk.”. Two entities had far more than 15% of the group’s total risk exposure, while seven had less than 5%. - Unrelated Parties

Consolidated did not have any risks from unrelated parties.

Thus, Judge Holmes noted that Consolidated fails its own test. Moreover, this test assumes that the risks were sufficiently unrelated, and they were not. The expert at trial compared the Caylor entities’ dependence on Caylor Construction to “having a bunch of mice on one side and an 800-pound gorilla on the other with no way for Consolidated to balance the risk that Caylor Construction carried compared to the other entities.”. All of the Caylor entities operated within the same or similar industry, which further illustrates a lack of risk distribution.

Insurance in the Commonly Accepted Sense

The requirement that insurance companies provide insurance in the “commonly accepted sense” is somewhat subjective, but Judge Holmes noted (citing the prior Avrahami case)that there are at least four key considerations: 1) “whether the company was organized, operated, and regulated as an insurance company;” 2) “whether the policies were valid and binding;” (3) “whether the premiums were reasonable and the result of an arms-length transaction;” and (4) “whether claims were paid.”

- Organization, Operation, and Regulation

The expert testified that “he had never seen a real insurance company issue policies after the period being insured.” Another expert testified that she had never seen another company “[back] into the premium amount the way Consolidated and Tribeca did.” Moreover, the claims administration process from 2009 left much to be desired. Tribeca sought more information, as a typical insurance company would, when a claim was made. However, “instead of giving that information, the policyholders just told Consolidated to pay, and Consolidated obeyed.” Don’t we all wish that every commercial insurance company would do the same? - Valid and Binding Policies

Noting the unusual and uncustomary timing of policy issuance and pricing, Judge concluded that “[t]he ‘policies’ provided by Consolidated are the most glaring evidence it wasn’t an insurance company.” He continued noting that “[d]uring the years at issue, Consolidated… didn’t provide policies for the Caylor entities until after the claims periods ended” and “[t]he Caylor entities paid premiums to Consolidated without knowing the total premiums for each and without knowing what those policies would be for that year. Two claims were even paid on policies that had not yet been written… A policy written after the claims period is being written after there is no longer a risk of loss, which defeats the whole purpose of insurance.” - Reasonable Premiums

On the point of whether or not premiums were reasonable, the court had two concerns, one macro and one micro. The macro issue was that the premium payments did not reflect the Caylor testimony that they sought coverage through Consolidated that they were not able to obtain through traditional commercial insurance. The amount that the Caylor entities spent on premiums far outweigh the amount resulting from uncovered losses before the captive was established. The court writes “[w]hile we don’t think that any premium over $50,000 per year would be per se unreasonable, a premium that is so much higher – $1,150,000 higher to be specific – looks unreasonable and thus likely to be for something other than ‘insurance’ as that term is commonly understood.” The Caylors were not able to offer sufficient evidence to explain and justify the massive increaseAt the micro-level, the judge found that the calculation of the premiums was questionable at best. “Rather than starting with the Caylor entities’ historical losses – which credible testimony showed would have been standard practice in the industry – Tribeca started with the total premium amount the Caylor entities as a whole wished to pay, and then created and priced policies that would fit within this limit. This caused one of the expert witnesses to note that Consolidated and Tribeca were “backing into” these premium amounts. Moreover, there was no indication that these amounts took into account any of the Caylor entities’ loss history, regardless of how long or short that history was.

The judge also noted that, while they did start with the Insurance Service Offices base rate, so many adjustments were made to this rate that it became virtually unrecognizable. And these adjustments clearly were made in order to inflate the premium amounts to $1.2 million. For example, Tribeca used something completely unheard of in traditional insurance: the “captive risk factor,” which Tribeca said was for “inflat[ing] premiums to allow captives to grow in financial strength.” The court found that “the premiums weren’t actuarially determined, and their parameters and assumptions were not properly documented.” This is clearly not how real insurance companies commonly operate.

- Payment of Claims

As previously noted, the claims administration process was also anything but conventional. Again, Tribeca requested information to verify two claims – as is typical of the industry – but never received adequate documentation. Consolidated mysteriously (or not so mysteriously) paid the claims anyway.Not surprisingly the court concluded that because Consolidated “calculated premiums in a fanciful way in entirely unreasonable amounts, issued claims-made policies after the time to make claims had expired, and paid the few claims that it did on the say-so of its clients… [it] did not operate like an insurance company.”

Conclusion

Consolidated did not have adequate risk distribution nor did it behave like an insurance company in the commonly accepted sense. Thus the court rightfully concluded “the premiums paid to Consolidated and deducted by the Caylor entities [were] not ‘insurance’ for federal tax purposes.” (*49).

Takeaways

- A captive must stem from an insurance need. While it is not technically a problem for the hope of tax benefits to play a factor in the captive decision, entering into a captive insurance arrangement should be first and foremost an insurance-motivated transaction.

- Risk distribution among a large number of risk exposures is essential.

- Captives should not engage in practices that commercial insurance companies never would—such as accepting premiums before underwriting is completed and paying claims without evidence to support the loss.

- Premiums must be actuarially determined or at least actuarially There must be a justification for everything, especially if they involve large payments.

- A captive is an insurance company, so use it as such. File claims for actual losses, and not only after the IRS audits you.

- Ensure that each insured entity is independently and directly underwritten.

About the Author

Jayna is a law student interning with CIC Services LLC for the summer of 2021. She attends the University of Colorado Law School in Boulder, where she aspires to work in tax and environmental law. She is a member of Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated summa cum laude from Austin College where she received her B.A. in both mathematics and philosophy. Jayna has been researching captive insurance law since 2015, and hopes one day for the opportunity to advocate for small business captives.

Jayna is a law student interning with CIC Services LLC for the summer of 2021. She attends the University of Colorado Law School in Boulder, where she aspires to work in tax and environmental law. She is a member of Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated summa cum laude from Austin College where she received her B.A. in both mathematics and philosophy. Jayna has been researching captive insurance law since 2015, and hopes one day for the opportunity to advocate for small business captives.